Braid and LIMBO are the poster children of indie games. They’re the ones everyone plays, but they’re gateway indie games. From there some will move onto the harder stuff, fully detaching themselves from the “mainstream” and sneering at anyone ignorant enough to enjoy Call of Duty.

My indie inclination began, as it so often does, with Braid and LIMBO, but the candy that finally lured me into the indie game unmarked van was The Binding of Isaac.

With Super Meat Boy co-creator, Edmund McMillen, at the helm, The Binding of Isaac is a twisted little title that blends dark humour, a creepy aesthetic, and addictive gameplay elements from dungeon-crawling RPGs and old-school arcade shooters.

The game parallels the Bible story of the same name, in which God tests Abraham’s faith by asking him to sacrifice his son Isaac. As Abraham prepares to commit the deed, God intervenes at the last moment, declaring it a rather douchey test of faith.

The game begins with a cute little animation detailing that story, minus the divine intervention. Isaac escapes his mother’s holy wrath by fleeing into the basement, where he must fight deformed, childlike, increasingly-disturbing enemies, and eventually, defeat his mother.

As expected, the game is full of religious references. Biblical iconography is rich ground for games to explore, but many won’t, as it courts controversy – Isaac’s Nintendo 3DS port was cancelled at the last minute due to concerns of blasphemy.

Beyond religion, the game is largely about childhood, told in a deeply personal yet universal manner. It exhibits a childish humour in bodily fluids; demonstrates a hyperactive imagination; presents the parent as a Godlike figure; touches on sibling relationships; and plays on familiar childhood fears of monsters hiding in the dark, of not fitting in, growing up, loss, pain and death.

The way the game combines elements of these two themes makes for a fascinating world, unique among games. Isaac uses items that are either Biblical artefacts – the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Crown of Thorns – or traumatic childhood memories – the severed head of his dog, the spirits of his siblings. He fights enemies with traits, names and designs along the same lines: among what seem to be his deformed brothers and sisters, Isaac faces the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse and personifications of the Seven Deadly Sins.

There are some truly dark moments, involving themes that are not often examined in video games: during later playthroughs, Isaac journeys into his mother’s womb and fights an unborn fetus, dragging up uneasy implications of abortion.

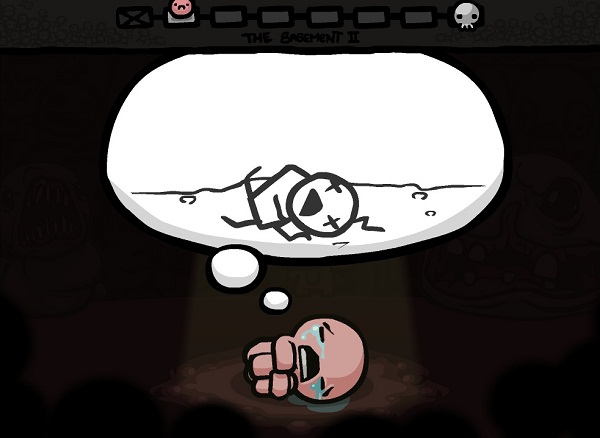

There’s not a lot of direct storytelling, but we slowly come to know Isaac far more intimately than most video game characters. We see his fears through thoughts and dreams as he lies in the cold darkness, shivering, crying. His extreme vulnerability makes him one of the most sympathetic characters in gaming: his only defense is his own tears, and when he dies, he loses everything. Hell, even increasing his strength via power-ups carries a gruesome price: new abilities will transform Isaac physically, often through painful injuries. Collect a few, and soon Isaac will be a gnarled, barely-recognizable mess.

Everything that happens to him is entirely undeserved, and this is where the game design feeds back into the themes. Randomly-generated dungeons supersede the forgiving hand of a designer, meaning that levels are often unfair. You found a golden door, no doubt hiding sweet loot, but there’s no key in the level to open it? Sorry kid, life’s not fair. Game design, and by extension gamers, take for granted that for every obstacle there’s a way around it, but that’s not always how things work.

This occasional unfairness harks back to the early days of gaming, when built-in challenge could all but break players, but success was all the more satisfying as a result. It borrows elements from two old-school, notoriously-difficult genres: arcade, twin-stick, bullet-hell, shooter games like Ikaruga or Geometry Wars, and dungeon-crawling RPGs like Baldur’s Gate or the early Zelda games.

Randomization and perma-death encourage repeated playthroughs, and conjure memories of arcade game design. It all contributes to the game’s addictiveness: a different layout every playthrough means that victory always feels just out of reach. Died? The next try could give you good stuff. Died again? Well, maybe the next one. Or the one after that.

Wrapped around that addictive gameplay core is a great visual style, very characteristic of Edmund McMillen. If you’ve seen Indie Game: The Movie, you’ll recognize his personality and style, which the film explores in relation to his previous project, Super Meat Boy. He discusses a love of drawing monsters as a kid, and the artwork shown looks very familiar – obviously McMillen was in his element designing the disturbing creatures Isaac faces.

Perfectly complementing the visuals is Danny Baranowsky’s haunting soundtrack. Reviewing games, I always have the most trouble discussing the sound design. I just don’t have the musical vocabulary to explain why I like or dislike something. But even to someone as musically handicapped as myself, Baranowsky’s compositions perfectly capture the emotions of the game: each piece of music is at once mysterious, ominous and unnerving.

The Binding of Isaac has all the hallmarks of a great indie title: it’s modest in scope, with massive replay value, genuinely addictive gameplay, and an incredible art style and soundtrack. But its appeal runs deeper than that: it feels like the most personal game I’ve ever played. Isaac’s fears are relatable, and in revealing them, McMillen has bared his soul creating this game.